Currently, there are no clear policies or legal provisions on approved alternative uses of aflatoxin-contaminated food in Kenya, neither are there approved disposal methods.

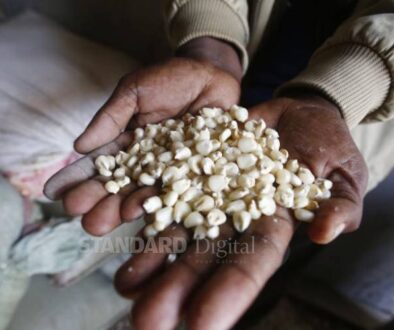

And with the sustained threat of aflatoxin contamination in major food commodities such as maize, groundnuts, milk, cassava, and cottonseed, among others, it becomes prudent that the Government responds by establishing measures that limit these foods’ exposure to consumers.

The occurrence of aflatoxin above the set limits, which is currently 10ppb for both foodstuffs and animal feed in Kenya, renders most commodities unfit for the intended purpose, whether it is for consumption by humans or livestock.

The heightened sampling and testing of such susceptible products coupled with the regulatory recalls and withdrawals of aflatoxin-contaminated commodities has confined contaminated supplies to manufacturing and business stores as well as research institutions and cereals pending amicable agreements on alternative use or disposal.

While this seems to be a significant problem, there is a simple and straightforward solution. Owing to the inability to eliminate aflatoxin entire from the food sources, such commodities unfit for a particular use can be channeled for alternative uses that require less stringent aflatoxin requirements, that is, being processed into a byproduct compliant with the aflatoxin limits.

For one, it is worth noting that the severity of risk from aflatoxin differs substantially between humans and animals, which means some of the contaminated foods can be appropriately placed for the alternative use of animal feed and energy production.

However, the current standards set for the permissible levels of aflatoxin need to be reviewed and increased to match the global standards to ensure no massive wastage of foods people depend on for consumption and as a source of income.

Through chemical and physical processing, aflatoxin-contaminated commodities can be processed to yield byproducts that become fit for animal consumption – which can be selectively used as animal feed for the appropriate type and category of livestock – as well as the manufacture of industrial products such as ethanol.

In the United States, the main source of ethanol fuel is obtained from corn biomass the fermentation and distillation of ethanol. Nothing is preventing Kenya from adopting this alternative use of aflatoxin-contaminated maize. However, this does mean that there should be a dedicated plant for producing ethanol. It has already been established through private sector analysis that such a move will result in poor returns on investments owing to the challenge of determining the exact quantities of contaminated grain.

If this move is to be adopted, sugar millers already producing ethanol from sugar cane should also consider using contaminated maize to produce ethanol with their existing plants. This strategy will reduce the need for a dedicated plant for ethanol production from maize alone. Similarly, ethanol production should be considered a feasible project for the East African Community as this will encourage the countries involved to export the contaminated maize to such plants to produce ethanol hence avoiding cross-contamination with human consumption.

Apart from ethanol production, aflatoxin-contaminated foods can also be used in the production of starch for industrial purposes. This will not only offer a solution to the unsafe commodities but also give local companies producing starch an advantage over the cheaply imported starch coming into the country. As such, the government must consider the introduction of the appropriate level of duty on imported starch to incentivize local companies to produce starch locally and utilize contaminated maize.

Of course, before such measures are taken, there is a need to review and modernize the existing permissible standards practices, and alternative uses of contaminated commodities to maximize their potential economic value, while also protecting public health.

Priorities should be given to the opportunities to produce energy through biomass, in the modernization process of alternative uses. This will also provide leeway to supporting initiatives to address the different needs of formal and informal trade and agriculture, which will influence the effectiveness, sociocultural relevance, and economic viability of proposed alternative use and or disposal systems.